Assault weapons are generally semi-automatic rifles, shotguns, and pistols that accept detachable magazines and possess certain military-style features, such as folding stocks and pistol grips, as defined in various state laws and the federal assault weapons ban that was in place from 1994 to 2004. Many designs and features of assault weapons marketed and sold to civilians are based on those of assault rifles carried by soldiers and used in combat, but the two terms aren’t exactly interchangeable, as discussed below.

Much more important than the terminology, however, is the fact that assault weapons have been used to commit the deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history. These firearms are deadlier than more traditional weapons, like hunting rifles and shotguns, for a number of reasons, but especially because assault weapons can accept high-capacity (or large-capacity) magazines, which hold 10 or more rounds of ammunition. High-capacity magazines allow shooters to fire anywhere from 10 to 100 shots before reloading to inflict more casualties.

Research indicates that over twice as many people are killed when mass shootings involve an assault weapon and/or a high-capacity magazine. Yet these weapons of war have become a staple of the gun industry’s sales and marketing to civilian consumers.

The Rise of Assault Rifles

The World Wars brought about many lethal small arms innovations, such as the Thompson submachine gun, or “Tommy gun,” which was invented in 1918 for the U.S. military. The Thompson is a select-fire weapon, giving soldiers the ability to fire the gun in either semi-automatic mode — after firing the first shot, the gun automatically loads a fresh round from the magazine into the chamber, but the shooter still has to pull the trigger to fire again — or fully automatic mode, where the gun continues firing as long as the shooter depresses the trigger and the gun has ammunition. The Thompson eventually found its way into the hands of gangsters, informing why Congress enacted the National Firearms Act of 1934 to make it very difficult for civilians to own full-auto-capable weapons (i.e., machine guns), silencers, and other dangerous items.

Toward the end of World War II, the Nazis developed the world’s first assault rifle, the Sturmgewehr 44. A select-fire weapon, it was designed to fire intermediate cartridges from detachable 30-round magazines. “Intermediate” here means the ammunition was larger than the pistol rounds at the time but smaller than the rifle rounds the German military had been using, allowing soldiers to carry more ammunition. The intent was to give Nazi soldiers more firepower — more ammunition to fire rapidly — to assault enemy positions. Sturmgewehr literally translates to “storm rifle” or “assault rifle.”

Most German soldiers were issued bolt-action Kar98k rifles with wooden stocks and internal five-round magazines in WWII. To reload, they had to push five rounds, held in a stripper clip, down into the gun’s action. But the Sturmgewehr used detachable 30-round magazines, significantly increasing the amount of ammunition available and making it much quicker and easier to reload the gun. And unlike most other rifles that came before it, the Sturmgewehr had a “pistol grip” — so named because it resembles a pistol’s grip, which is more vertical than a traditional rifle’s — separate from the shoulder stock for better maneuvering in close quarters and easier one-handed operation. The barrel was also protected by a handguard, or shroud, allowing soldiers to grasp the gun with their nondominant hand without being burned, and the muzzle was threaded for the attachment of rifle grenades.

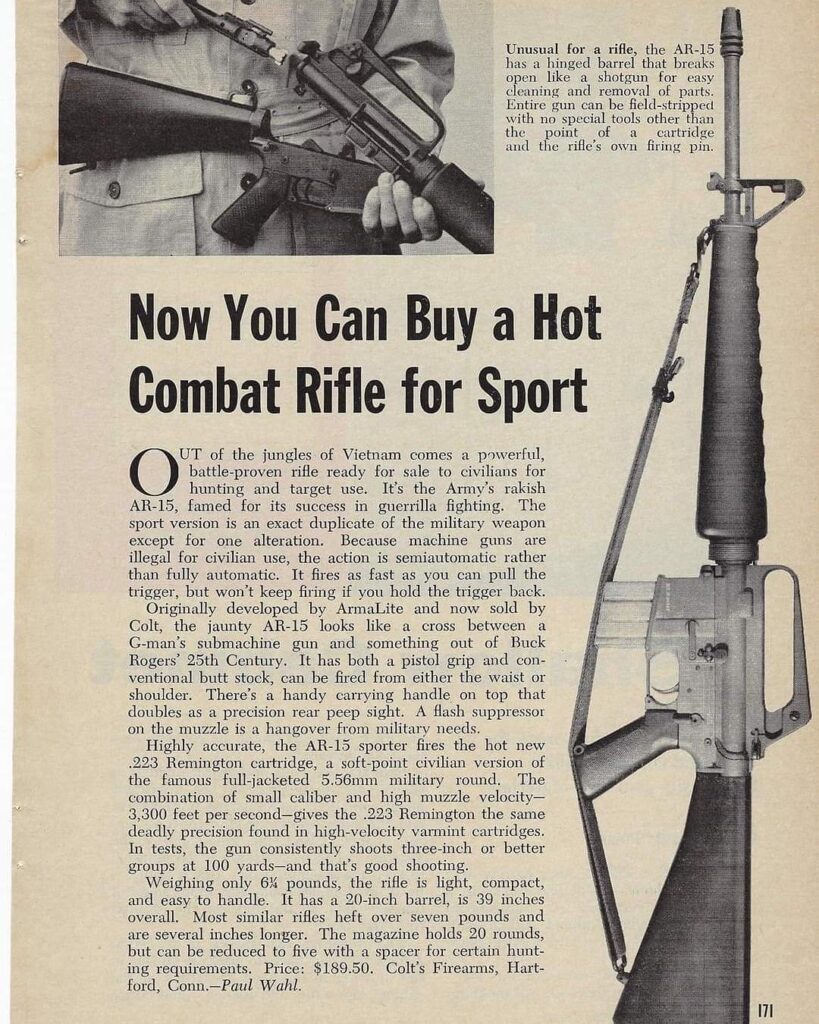

The Sturmgewehr saw limited use in WWII, but afterward, several countries began searching for their own select-fire assault rifles. For example, the Soviet military adopted the AK-47, which shared many design characteristics of the Sturmgewehr, including its use of curved 30-round magazines, in 1947. The FN FAL and Heckler & Koch G3 were developed in Belgium and West Germany in 1953 and 1958, respectively. And in the U.S., a company called ArmaLite began developing the AR-10 (ArmaLite Rifle Model 10) that was made of steel, aluminum, and plastic to save weight. When the U.S. military began looking for a smaller-caliber rifle that allowed soldiers to carry more ammunition, ArmaLite scaled the AR-10 down to create the AR-15 chambered for .223 Remington ammunition.

Like the earlier Sturmgewehr, the AR-15 used detachable magazines and featured a pistol grip separate from the shoulder stock, a handguard (or barrel shroud), and a barrel threaded for a flash suppressor, which helps eliminate muzzle flash, making it harder to determine a shooter’s position while preserving their vision in dark conditions.

ArmaLite sold its rights to the AR-15 to Colt, which began providing a select-fire version of the rifle — dubbed the M16 — to the U.S. military in 1964 with 20- and eventually 30-round magazines. (A year earlier, the military adopted the .223 Remington cartridge as the “5.56mm M193,” which led to the dimensionally identical but higher-pressure 5.56mm NATO.) Colt also started offering semi-auto versions of the rifle, called the AR-15 Sporter, with five-round magazines to civilians in 1964. Later, 20- and 30-round magazines were introduced for civilians.

SEmi-Auto Versions of military weapons

After Colt’s AR-15 patent expired in 1977, other gun manufacturers, such as Bushmaster, DPMS, and Eagle Arms, began offering their own semi-auto versions to civilians. However, only an estimated 787,144 AR-platform rifles were produced for civilians from 1964 to 1994, compared to the millions of hunting rifles and shotguns produced during that same period.

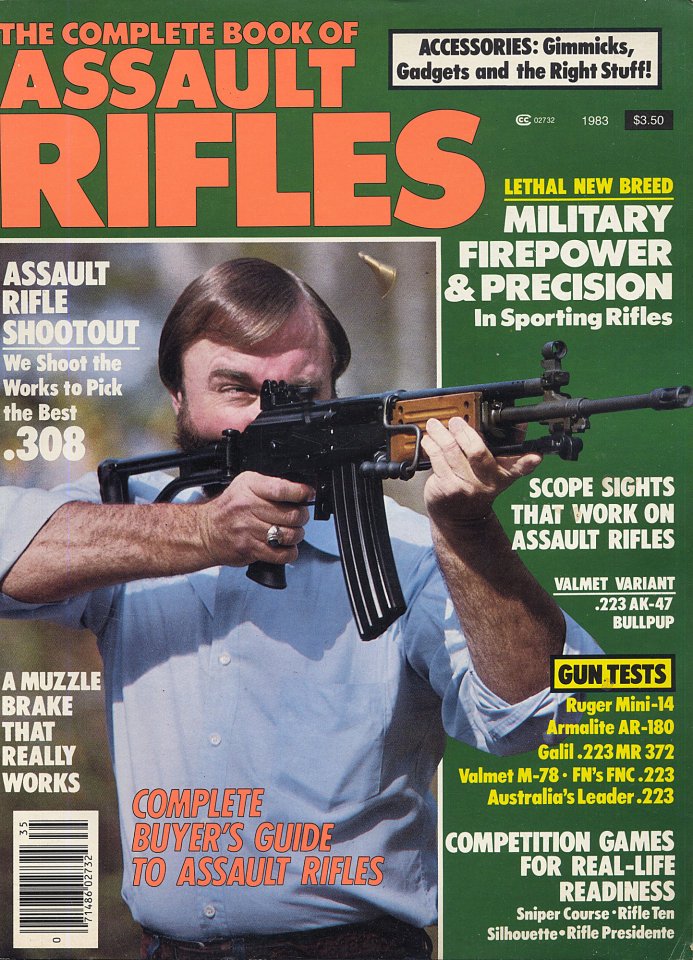

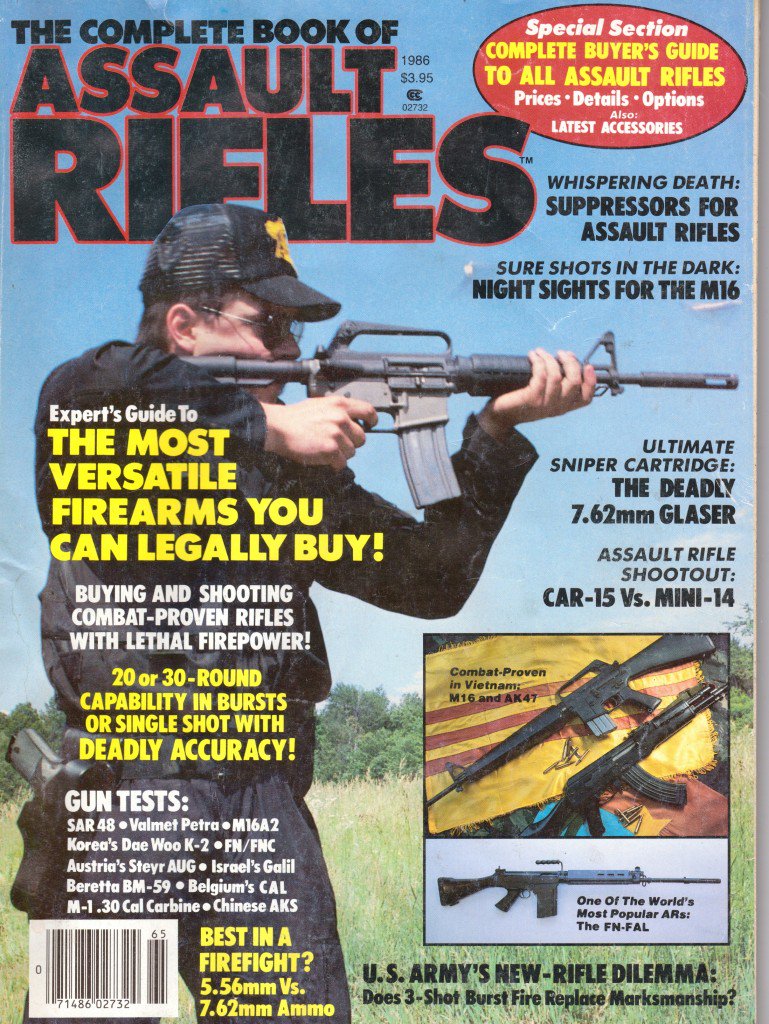

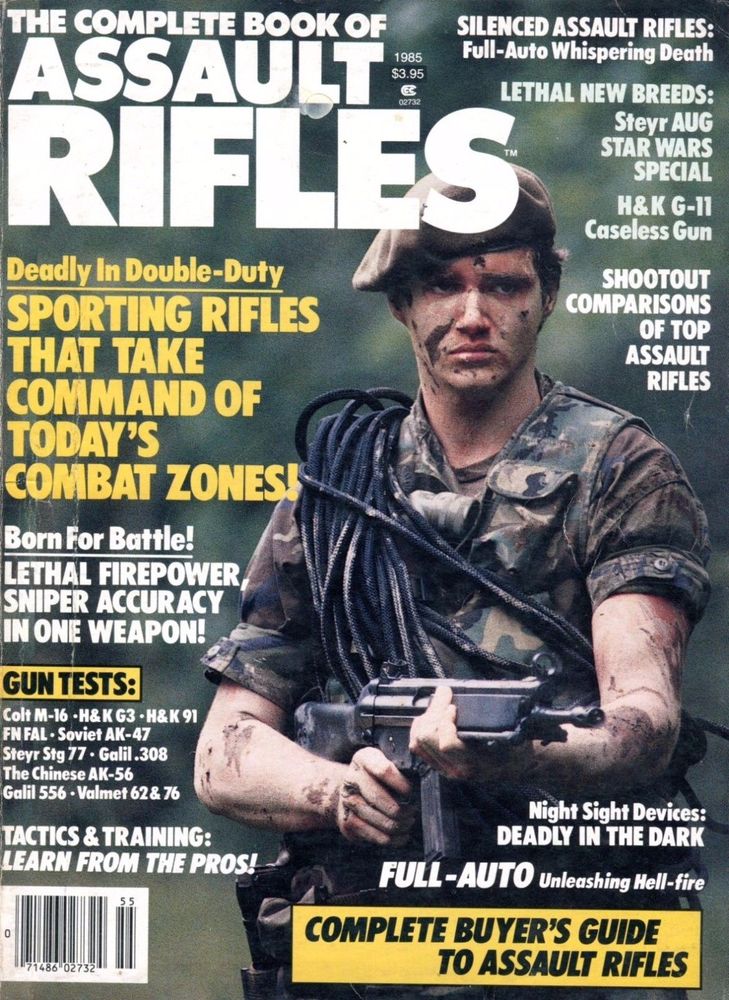

Other semi-auto versions of military weapons began hitting the U.S. market in the 1970s and 1980s, like the Israeli Uzi in 1980 and the first AK-47s, imported from China, in 1984. The 1980s also saw the rise of weapons like the TEC-9 and MAC-10, which were originally created as fully automatic weapons for military contracts before semi-auto variants were made available to American civilians.

Gun publications began showcasing weapons designed for military use alongside their semi-automatic derivatives for civilians, conflating the terms “assault rifle” and “sporting arms” in marketing military-style weapons for things like hunting and target shooting.

THe first assault weapons bans

“Assault rifle” is a military term that denotes a select-fire rifle that uses intermediate cartridges, such as the M16. Because they are capable of fully automatic fire, these firearms have been highly regulated since 1934. But it’s unclear where “assault weapon” — a policy term that usually describes a military-style, semi-automatic firearm like the civilian AR-15 — originated. Some say legislators in California first started using it in 1985 in connection with attempts to curb the rise in crimes committed with them. Others say the gun industry created the term a year earlier as a way to spark interest in military-style weapons.

In January 1989, a gunman used a semi-auto AK-47 made in China by Norinco to kill five children and wound another 32 at the Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California. This spurred California to enact the first assault weapons ban of its kind, the Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act (AWCA), in May 1989 — just a few months later — which outlawed 50 specific firearm models by name. New Jersey and Connecticut followed suit with their own similar assault weapons bans in 1990 and 1993, respectively.

In July 1989, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) released a memo discussing the differences between military-style weapons and weapons suitable for “sporting purposes,” i.e., hunting and target shooting. As the memo noted, some states place limits on how much ammunition a hunter can carry into the field because hunting ethically means dispatching the game animal as quickly as possible, negating the need for a semi-automatic weapon that can accept large-capacity magazines.

Going further, the memo stated that, unlike sporting arms, military-style weapons typically accept detachable magazines and possess folding and collapsible stocks, pistol grips, bayonet mounts, flash suppressors, and grenade launchers, among other features — characteristics designed to increase their lethality. They’re also commonly semi-automatic versions of fully automatic weapons, as the ATF noted. The working group that drafted the memo relied on information provided by licensed hunting guides, state game and fish commissions, local hunting associations, competitive shooting groups, and hunting/shooting magazine editors.

Fast-forward to July 1993, when a gunman used two TEC-9 pistols to kill eight people and wound another six at an office building in San Francisco, in what was known as the 101 California Street shooting. Congress then enacted the federal assault weapons ban as part of the 1994 crime bill. The ban outlawed several guns by name — like the original California ban — as well as semi-automatic rifles, shotguns, and pistols that accepted detachable magazines and possessed at least two military-style features, as outlined in the ATF’s July 1898 memo. The law also prohibited the manufacture of high-capacity magazines after its enactment.

But the law grandfathered-in “pre-ban” firearms and magazines, and gun manufacturers quickly developed “post-ban” models that accepted detachable magazines and possessed only one of the features described in the law. For example, gun makers still sold AR-15s with pistol grips but fixed (non-telescoping) stocks and 10-round magazines.

Still, the ban was effective. While Congress allowed it to expire in 2004 — amid lobbying from the NRA and gun rights advocates — researchers estimate that if the assault weapons ban had remained in place, we’d see 70 percent fewer mass shootings deaths today.

THE MARKET EXPLODES — and shootings increase

After the assault weapons ban expired, the gun industry capitalized on weapons that looked and functioned like the M16 and shorter-barreled M4 rifles used by U.S. soldiers at the height of the Global War on Terror. Smith & Wesson unveiled its first AR-15s in January 2006. Around the same time, the Freedom Group, a large firearms conglomerate that owned Remington at the time, purchased Bushmaster and DPMS, which marketed AR-15s and larger-caliber AR-10s for combat, law enforcement, and hunting purposes, in 2006 and 2007, respectively. Many smaller companies formed to produce AR-platform weapons or parts allowing owners to customize them.

In 2009, the firearms industry’s trade association, the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), coined the term “modern sporting rifle” (MSR) to describe military-style, semi-automatic rifles in an effort to separate them from the “assault weapons” of the past. A year later, Ruger unveiled its first AR-15. In 2011, Smith & Wesson told its investors that the civilian “modern sporting rifle” market was worth an estimated $489 million, and the Freedom Group claimed that particular market segment grew by 27 percent from 2007 to 2011. As this market segment grew, so too did the number of people killed and injured by assault weapons in mass shootings.

Today’s assault weapons bans

While the federal assault weapons ban expired in 2004, several states and D.C. have their own bans in place. These laws all differ slightly, but most still prohibit specific assault weapons by name and then use a “feature test” to capture semi-automatic rifles, pistols, and shotguns that accept detachable magazines and have at least one military-style feature — as opposed to the original federal ban’s two, in an effort to prevent fewer loopholes — while also prohibiting high-capacity magazines.

The focus on high-capacity magazines makes sense because semi-automatic weapons operate much more quickly than manual firearms, such as bolt-action rifles and pump-action shotguns, making it easier for a shooter to fire off several rounds in rapid succession. Detachable magazines also hold more ammunition (up to 100 rounds in some instances) while being quicker and easier to reload.

The other assault weapon features outlined in these bans increase a semi-automatic weapon’s lethality and are not merely “cosmetic,” as gun groups often argue. For example:

- A pistol grip makes it easier for a shooter to operate the weapon with just one hand; maneuver the weapon in close quarters, such as tight hallways; and more quickly reload the weapon without taking it off their shoulder.

- A forward grip, or foregrip, allows a shooter to control the front end of their weapon better and mitigate recoil for faster follow-up shots. These aren’t used on traditional hunting rifles or shotguns.

- A folding stock (like those found on AKs) or collapsible stock that can be extended or retracted (like those found on ARs) make a weapon easier to conceal and use in close quarters. Again, these are not found on traditional rifles and shotguns, which have “fixed” stocks.

- A barrel shroud provides a gripping surface for the shooter’s nondominant hand, preventing it from being burned by the barrel and providing more control, especially in rapid fire. On today’s weapons, barrel shrouds also allow for the attachment of accessories like grips, lights, and aiming lasers.

- A threaded barrel allow shooters to install flash suppressors, which help eliminate the gun’s muzzle flash, making it harder to determine where a shot came from; silencers, which dampen the sound of gunfire, again making it difficult to determine where a shot originated; and muzzle brakes or compensators, which help dampen muzzle rise for faster follow-up shots.1See also Lanie Lee Cook, “What is considered an assault weapon?” Fox 31, June 8, 2022, https://kdvr.com/news/local/what-is-considered-an-assault-weapon/; and Margaret Hartmann, “What Makes a Gun an Assault Weapon?” New York Magazine, January 30, 2013, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2013/01/what-makes-a-gun-an-assault-weapon.html.

Individual state laws address other features, but because of these enumerated features, assault weapons are easier to aim and control, especially in rapid fire, than traditional handguns, while being more maneuverable than traditional hunting rifles and shotguns, increasing their lethality. These weapons are also easy to modify and customize with accessories for greater accuracy, concealability, and rates of fire.

AR-15s, AK-47s, and similar weapons also fire rifle bullets that, while smaller and less powerful than traditional hunting rifle rounds, travel significantly faster than handgun bullets. This high velocity translates to greater damage inside a person’s body, and these rounds can even pierce the handgun-rated bulletproof vests commonly worn by police officers.